A half-century ago this week, a budding American jazz pianist touring Europe made his way to Cologne’s opera house. That night, he hadn’t gotten much sleep; his back was bothering him. It was late—at 11:30 pm—and he was scheduled to perform an improvisational set before approximately 1,400 people. Compounding matters, a miscommunication resulted in him being provided with the incorrect instrument—a small practice grand piano known for sluggish keys, poor intonation, and unreliable high notes. To top it all off, he hadn’t eaten since earlier that day. Nevertheless, what ensued became one of the landmark performances in 20th-century music history.

By 1975

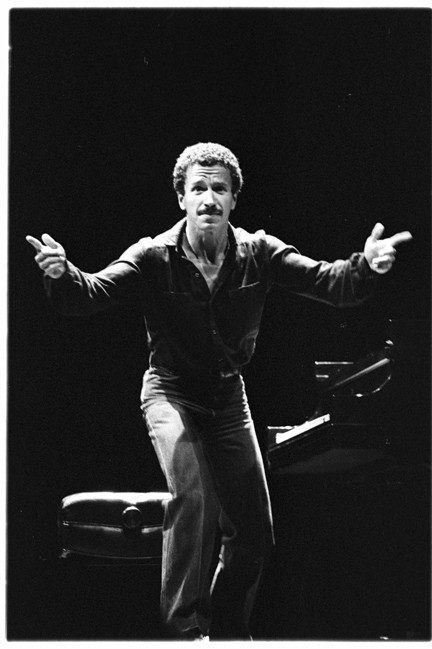

Keith Jarrett

He was already well-known within the jazz community, but his performance at an ominously foretold event in Germany transformed him into something exceptional for the jazz scene: a recognizable figure even to those not typically inclined towards jazz music. Featuring clear-cut melodies, compelling rhythms, and dazzling displays of skill seemingly pulled out of nowhere, “The Köln Concert” became the highest-selling solo piano record ever (with over four million copies sold so far). This achievement earned admiration for Jarrett from musicians like Vladimir Ashkenazy, Bruce Hornsby, and indeed, Adrian Chiles.

Today, Jarrett – who will turn 80 in May – can lay a legitimate claim to being among the world’s greatest living musicians, or perhaps even

the

greatest (a point compellingly made by author Geoff Dyer) — not only because of his individual accomplishments but also due to his role as a band leader and his interpretations of classical pieces. However, what truly encapsulates the essence and breadth of his contributions throughout a lengthy yet occasionally challenging career is the tale behind “The Köln Concert.” This performance embodies elements like risk-taking, confidence, and unyielding skill.

Jarrett was born on Victory in Europe Day in Allentown, Pennsylvania — the Rust Belt region prior to its widespread recognition as such — to parents who traced their heritage back to Slovenia, Germany, and Hungary. Even before reaching the age of three, his exceptional talents were evident. Jarret possessed absolute pitch and could navigate the keyboard effortlessly (“I used to sleep underneath it,” he shared in the documentary titled “The Art of Improvisation”). At just six years old, he performed his inaugural concert, adeptly taking on the persona of a young wunderkind with interpretations of works by Mozart and Bach. However, he also included two compositions of his own creation during this performance.

That independent streak would define his trajectory. In his teens he was invited to study composition in Paris with Nadia Boulanger – mentor to Aaron Copland and Daniel Barenboim, among many others – but decided against it, drawn instead towards jazz. So he went to Berklee College of Music, only to be kicked out. One story goes that he was caught playing a prize piano with vibraphone mallets.

Regardless, by the mid-1960s, he was earning his livelihood through jazz and rapidly advancing, performing with Charles Lloyd initially and subsequently with Miles Davis, all while fronting his ensemble. He emerged as an artist possessing remarkable adaptability—equally adept on the saxophone as at the piano—and showcasing eclectic musical preferences. His versatile nature also encompassed his ethnic identity. It’s reported that the saxophonist Ornette Coleman remarked, “Dude, you gotta be Black; you simply must be.” In response, Jarrett humorously stated, “Yeah, yeah, I get it. I’m trying my best here.”

Jarrett has always embraced a wide range of music without being overly critical. As someone who grew up during America’s mid-20th century emphasis on achievement, he believes that anything worthwhile is worth enjoying. Check out his heartfelt commentary on the Broadway hits from the 1920s and ’30s; tune into his rendition at the Dylan concert featuring smooth interpretations of “Lay Lady Lay” and “My Back Pages.” However, avoid listening to his 1968 folk-rock project titled “Restoration Ruin,” where he performs almost every instrument part himself and contributes lines like, “While the grass is gray / Ferns and bushes sway / For me.” It goes to show that even talented individuals might occasionally push their limits too far.

In the 1970s, he truly started forging his distinct path by collaborating with the visionary producer Manfred Eicher from ECM Records. He then embarked on a string of entirely spontaneous solo performances which he referred to as “epic voyages into the unknown.” Although this description could imply an indulgent psychedelic rock session, the resulting music was actually exquisite. As jazz became bogged down in endless debates among purists, experimentalists, and free-jazz advocates who competed to create sounds that were increasingly difficult to enjoy, Jarrett took a balanced approach. By blending various influences together, he created something remarkable yet deeply sincere.

This statement reflects his stance as well. In the liner notes for his album “Solo Concerts: Bremen/Lausanne” released in 1973, he stated that he was engaged in what he called an ‘anti-electric music campaign,’ with this piece serving as evidence against electric music. However, he went further to say, “Electricity flows through each one of us and should not merely be confined to wires.” This resistance towards electrified sounds—which he compared to consuming artificial vegetables—was supported by how his concerts unfolded. From the resonant spiritual calls at the concert held in Bremen to the grandiose “Sun Bear Concerts” staged in Japan in 1978—a series noted for their complexity—he crafted entire universes using only a piano.

Nevertheless, many people concur with Hanif Kureishi that “The Köln Concert” stands out as the pinnacle moment, encapsulating “the condensed essence of all Jarrett had experienced”: starting delicately—allegedly mimicking an opera house chime—the piece progresses through Part IIa’s blues-infused rhythm and Part IIb’s tempestuous shift, culminating in a spectacular finale. At times, listeners might ponder whether Jarrett truly improvises on the fly. Yet both Jarrett himself—”When Miles Davis queried how I could create music spontaneously, my response was simply ‘you just do it'”—and our own auditory experiences affirm his spontaneity. Despite its meticulously crafted structure, the performance includes stretches where Jarrett seems to cruise slowly before accelerating into full flight. Witnessing him navigate these transitions adds depth to what makes his performances captivating.

Of course, Jarrett has his critics. Many view his solos — which frequently derive from just a few chords instead of the intricate progressions common in jazz — as uncomfortably similar to easy-listening music. In “The Sopranos,” when Tony Blundetto tries to turn legitimate post-prison, he describes his concept for a massage parlor featuring Jarrett’s music. Additionally, some people dislike him due to his personality traits, including his inclination towards pseudo-spirituality. Jarrett gained infamy for his cantankerous behavior, regularly interrupting shows whenever an audience member dared to make even a slight noise, all while generating considerable commotion at the piano through stomping, whooping, moaning, and shrieking noises (a past YouTube clip compared these sounds to those made by Eric Cartman in “South Park”).

Critic David Hajdu wasn’t the only one who dismissed these actions as mere arrogance from a self-centered “jerk” who failed to recognize how off-putting his egotism could be. However, I find myself somewhat sympathetic toward Jarrett’s argument: “All I ask is for the listeners to perform a few straightforward tasks so I can focus,” he stated during an interview. Additionally, what he returns is substantial. During my attendance at his performance at the Royal Festival Hall in 2008, there occurred a small outburst. Upon spotting a camera flash, Jarrett abruptly rose from his seat at the piano and spent several minutes scolding the crowd. “What

is it

“About this world that requires an appearance?” he grumbled. However, he reclined back into his seat, picked up precisely from where he had paused earlier – and concluded with four additional performances as encores.

The biggest challenge Jarrett faced was his health. That evening in Cologne, he felt quite unwell. During the 1990s, he battled chronic fatigue syndrome, which sidelined him for several years. However, he staged an impressive return, delivering energetic performances both as a solo artist and alongside his Standards Trio over the next twenty years. As noted by Dyer, throughout his latter career, one wouldn’t attend his concerts merely because they were featuring Jarrett; rather, audiences expected to experience something uniquely extraordinary. Yet, in 2018, Jarrett encountered an insurmountable hurdle — two strokes.

Jarrett became unable to use his left arm and has not played music since then. This is an excruciatingly touching conclusion for many; however, it seems like he is facing this situation with a particular dry resilience. During a 2023 conversation with YouTube personality Rick Beato, they watch footage of him performing impressively back in the ’80s. “It must feel good to listen to,” remarks Beato. “Yes, but hearing myself now makes me realize I once had extra hands,” responds Jarrett humorously, referring to having just one additional hand functional at that time.

It’s important today to recall that even if he had stopped writing after 1975, his contributions would still be significant.

Subscribe to the Front Page newsletter at no cost: Your daily briefing on today’s key events provided by The Telegraph, delivered directly to your mailbox every day of the week.