Epic. The word epitomizes the gifts of a nonpareil American actor of stage and screen, a towering figure who shook solar systems as the voice of Darth Vader, who rattled Broadway’s rafters as Troy Maxson in “Fences,” who regularly delivered captivating turns, whether as the Moor of Venice, the prize fighter of “The Great White Hope,” the reclusive sage of “Field of Dreams.”

Was there ever a performance by James Earl Jones that didn’t offer evidence that giants walk the earth?

His elemental power found satisfying expression so often through the decades that

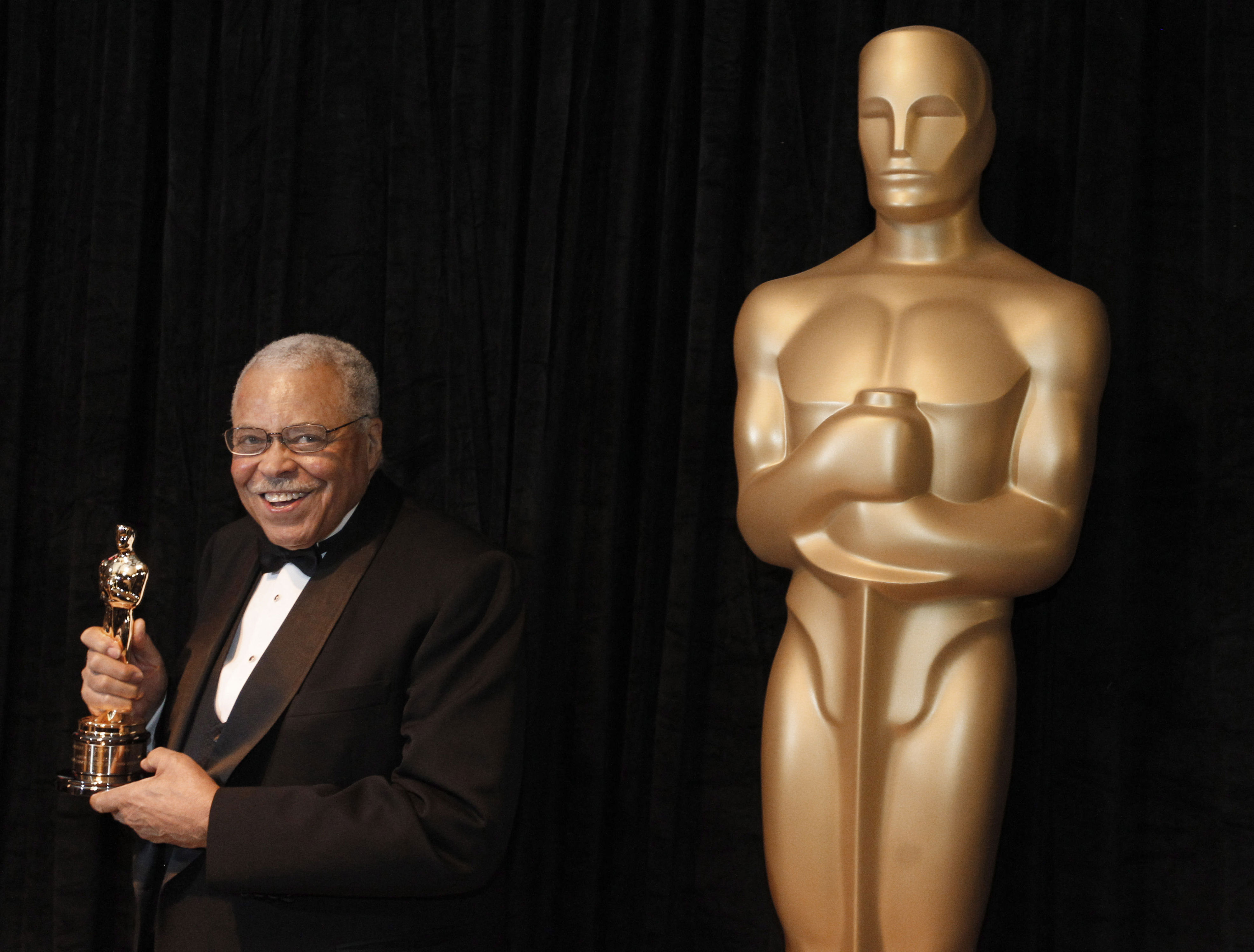

Jones, who died Monday at age 93

, became a go-to source for assignments that registered as consummately authoritative. Disney needed a regal sound for Mufasa, the reigning monarch of Pride Rock, in the original animated “The Lion King”? Ted Turner required the voice of a basso deity to intone his network’s lead-in and sign-off, “This is CNN”? Directors wanted a personality that radiated command, in films such as “Clear and Present Danger” and “The Hunt for Red October”? Whether it was a kingship or an admiralty, Jones seemed born to play it.

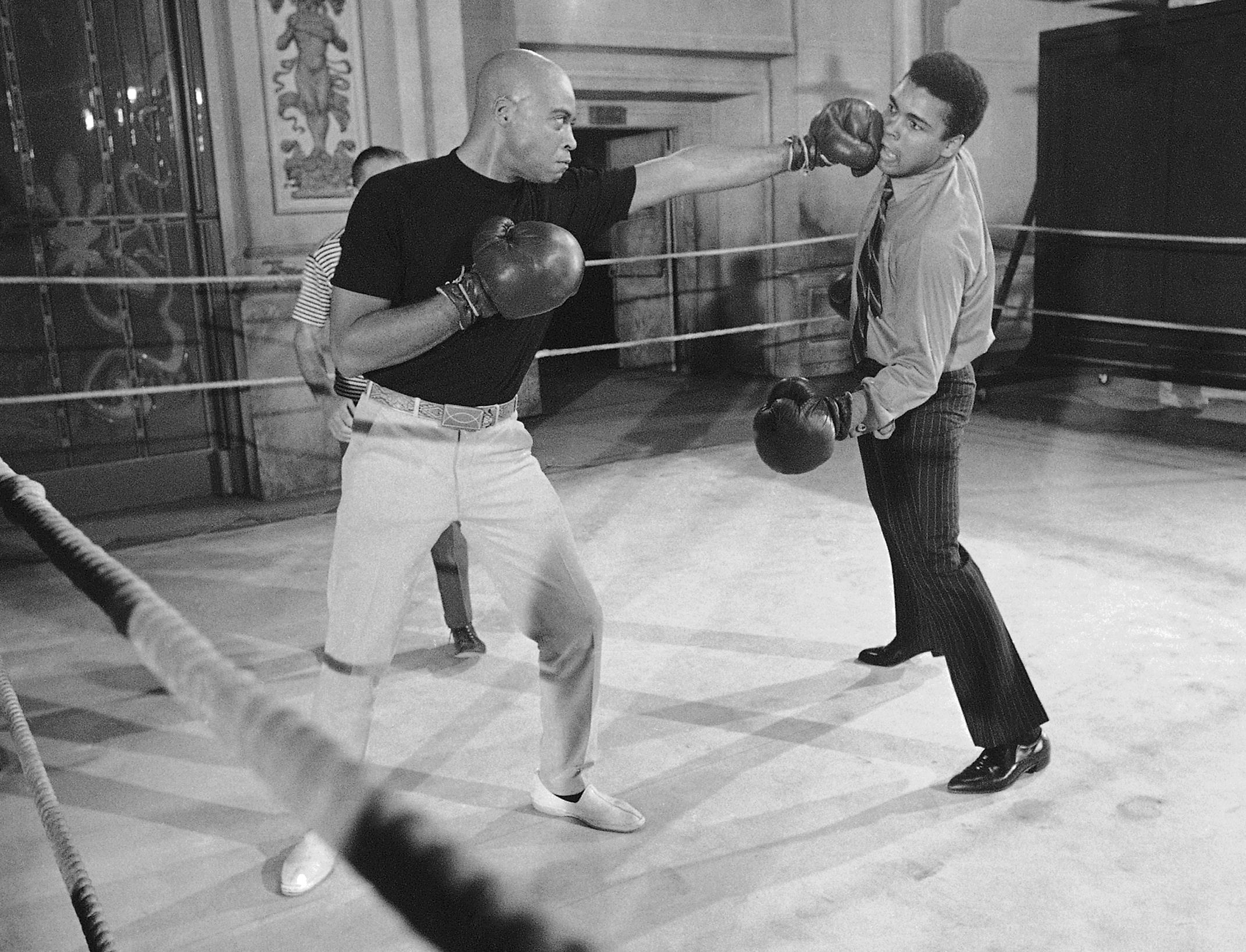

Of course, Jones’s influence went far beyond what his singing talents alone could unlock. He gained significant recognition in 1967 when he performed at Washington’s Arena Stage in the groundbreaking world premiere of “The Great White Hope.” This was Howard Sackler’s acclaimed drama destined for Broadway and later awarded the Pulitzer Prize. The story delves into the racial discrimination faced by Jack Johnson—referred to as Jack Jefferson in the script—the pioneering African American boxer who became the heavyweight champion.

Still,

As he informed me when presenting him with Kennedy Center Honors in 2002,

Although he didn’t see himself as a symbol of identity politics, preferring instead to view himself simply as an actor who happened to be Black, he found it amusing when fellow actors started copying his “Great White Hope” hairstyle by shaving their heads. He stated during an interview in a Georgetown hotel room, “I dislike the term ‘race.’ Being Black or having an ethnicity is clear enough; however, race creates divisions among people.”

Maybe it was the challenges he encountered during his upbringing in Mississippi and Michigan with his maternal grandparents that fostered within him an unshakeable sense of self-worth, defying conventional categorization. Surprisingly, considering his life story, he struggled severely with stammering as a child—so much so that he considered himself almost speechless until age 14. In high school, however, he discovered his voice amidst the beauty of literary works. “Through poetry,” he shared, “I started speaking another tongue, one filled with round Rs: Longfellow, Shakespeare, Chaucer.”

It appeared that his sanctuary lay in the intellectual universality found within the works of the authors he grew fond of. Thus, it comes as little wonder that one of the most compelling roles throughout his acting journey was bestowed upon him by none other than the renowned 20th-century theatrical mastermind, August Wilson. “Fences” stands out as Wilson’s most cherished drama, with Troy—the disgruntled garbage collector plagued by remorse and enveloped in disillusionment—emerging as the playwright’s quintessential tragic protagonist.

Jones delivered an outstanding performance in the 1987 original Broadway production, which was helmed by director Lloyd Richards. This role secured Jones his second Tony Award for Best Actor — “The Great White Hope” had previously won him his first. Most importantly, this role showcased the versatility of Jones’s acting abilities. I recall very clearly the peak moment when, compelled to face the enormity of his failings as both a man and a father, Troy swings a baseball bat at his son, Corey, portrayed by Courtney B. Vance.

The situation was too much for Jones. He implored Wilson to clarify that Troy would never genuinely swing the bat at Corey. Faced with hesitation from Wilson, he collaborated with Richards to devise a physical signal indicating that Troy had no intention of following through and striking him. “At the very least,” Jones shared with me, “I could exit the stage assured that I wouldn’t end up killing my own child.”

The admission highlighted an actor who thoroughly immersed himself in the personal aspects of a intricate character. However, he showed somewhat less dedication when it came to discussing contracts. Jones remembered that during the production of the initial Star Wars film — which went on to gross approximately

$775 million at the global box office

— He received $7,000 for it. Furthermore, the Darth Vader recording session went on for just 2½ hours.

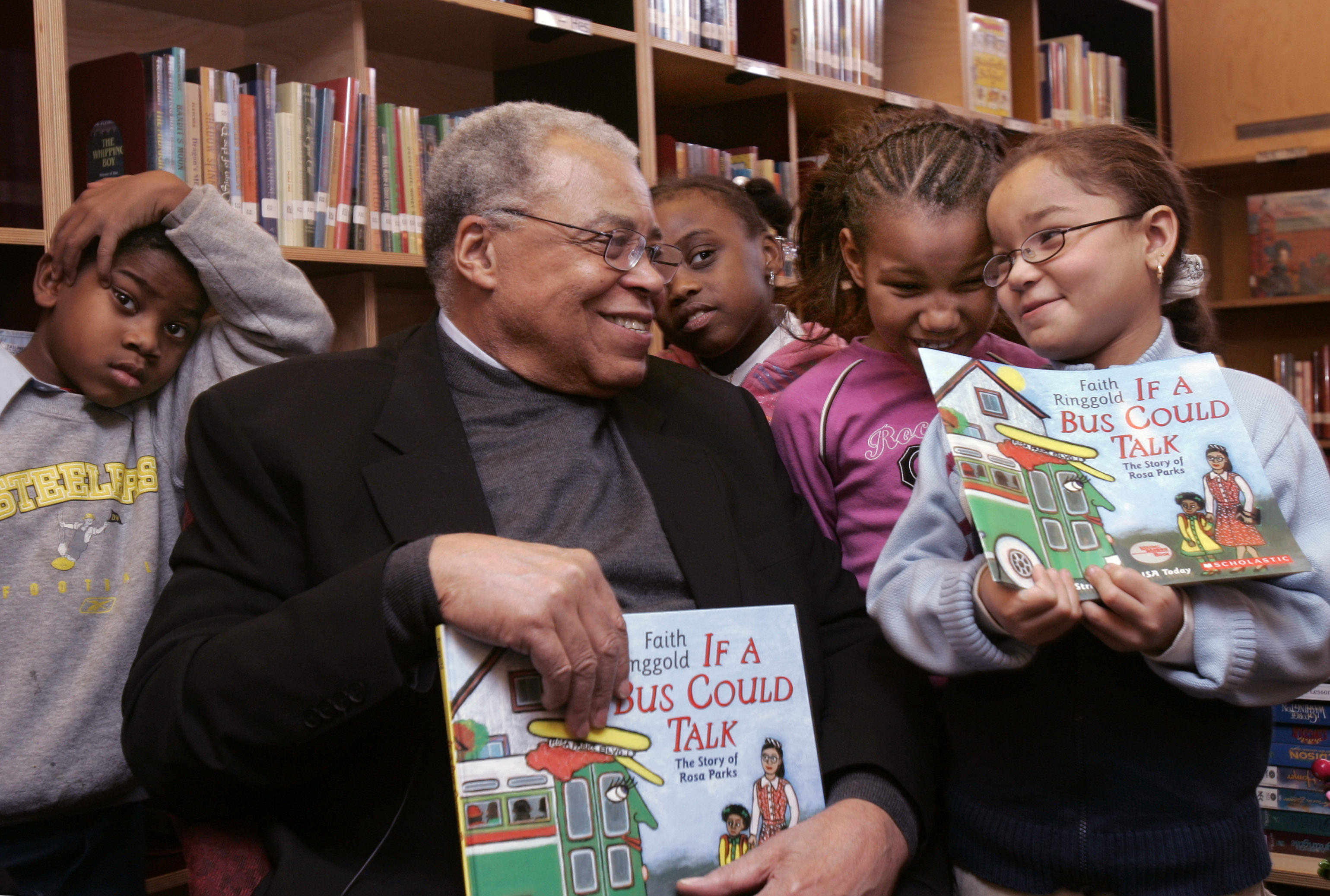

Twenty-one Broadway productions, along with numerous other plays, films, television shows, and voice-over work make up an impressive resumé—a record that reads as a comprehensive overview of American entertainment spanning six decades. Despite this, meeting him personally revealed someone disarmingly down-to-earth, even until we said goodbye, at which point he charmingly requested a photograph with me.

“A Shakespearean stage director once told him, ‘Avoid squandering your vitality by portraying a king. Instead, play a mere human,’ ” and this advice left an indelible mark on James Earl Jones.”